28. Classes and Objects#

As we mentioned earlier, everything in Python is an object. Objects are a special data structure that contains state (data/properties) and behavior (code/methods). Objects represent a unique, specific instance of something - typically what we think of as a “noun”. The state models the attributes of that “thing”, and the methods define the behavior and how it interacts with other “things” (objects).

This notebook series started with imperative programming - just sequences of statements to execute. As we brought in functions - organized code blocks, reusing code to perform a task - we morphed into procedural programming. Procedural decomposition involves dividing a larger action into smaller actions. We used procedural decomposition to avoid code repetition where the same task was performed in multiple places in the same code file and reusing functions through importing modules. We also used procedural decomposition to provide structure. By treating several tiny steps as a unit, we abstracted that functionality and made it easier to remember and use.

Object-oriented programming is a style of programming focused on objects. We create objects and tell them to do stuff by calling functions that belong to those objects. We typically refer to those object functions as methods. When two objects interact by calling methods and receiving return values, you may hear this called passing messages. The sending message is the method name and the associated arguments. The response message is the return value(s). With object-oriented programming, we reason about a program as a set of interacting objects rather than a set of actions(procedural programming).

Objects are instances of a class. A class describes a type of object we might create. Classes correspond to nouns - for example, a general category of something like a bank account or a stock. Classes then define the fields (state) that the object will have. They also define the behavior by defining methods within the class definition. Methods declarations are just function definitions within a class declaration. A class forms a blueprint from which we create objects.

While we can organize data and functions into modules, we can only have one instance of that module. With classes, we can have virtually unlimited instances (objects), each with potentially different attributes but common behavior.

28.1. Defining a Class#

For Python, a class is the code containing the data attributes and methods for a group of similar objects.

A simple class:

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 pass

That code block has now defined a new class that serves as a type. A few things to note:

Just as “def” signifies we are defining a function, “class” signifies we are creating a class.

Rather than using all lowercase letters with underscores to separate words, Python uses “CamelCase” as the naming convention for class names.

As a class needs some content, the

passkeyword instructs the Python interpreter to do nothing for that statement.passis a null statement. In this particular situation, since a docstring was defined,passis unnecessary, but the following code will fail:

1class EmptyAccount: # Raises SyntaxError: incomplete input

Cell In[2], line 1

class EmptyAccount: # Raises SyntaxError: incomplete input

^

SyntaxError: incomplete input

We define a docstring to provide information to others (and ourselves a year later) to summarize the class purpose and behavior.

1help(BankAccount)

Help on class BankAccount in module __main__:

class BankAccount(builtins.object)

| Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system.

|

| Data descriptors defined here:

|

| __dict__

| dictionary for instance variables

|

| __weakref__

| list of weak references to the object

28.2. Initializing an Object#

We can create new objects of the class BankAccount with

1account = BankAccount()

account is an object of the type BankAccount:

1print(type(account))

<class '__main__.BankAccount'>

With the current definition for BankAccount, we have created a new type and can instantiate new objects. However, these objects have no defined behavior or state.

Python allows us to assign methods and attributes dynamically to an object, but that does not change the class definition.

So, for example, we can add state to an object.

1account.name='Checking Account'

2account.balance = 1_000_000.00

3

4print("{:s}: ${:,.2f}".format(account.name,account.balance))

Checking Account: $1,000,000.00

We can also define and assign a function to the object. However, that function can not easily access any member state variables.

1def print_information():

2 print("some output")

3

4account.show_information = print_information # Using "show" is intentional

5

6account.show_information()

some output

In the previous block, we declared a function. We then set account.show_information to reference that function definition. (Functions are a particular type of object in Python). Finally, we called the function.

The above code also has an issue in that we only created the state and behavior for just the object account. Therefore, if we create another object from BankAccount, the resulting object will be empty as the class definition for BankAccount is currently empty. I.e., we have a blank blueprint.

1another_account = BankAccount()

2print(type(another_account))

3print(another_account.name)

<class '__main__.BankAccount'>

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[8], line 3

1 another_account = BankAccount()

2 print(type(another_account))

----> 3 print(another_account.name)

AttributeError: 'BankAccount' object has no attribute 'name'

As we define a class, we need to define the state and behavior that objects of that class possess.

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 balance = 0.0

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id):

6 self.account_number = account_number

7 self.customer_id = customer_id

8

9 def show_information(self):

10 print("Account #{:d}: ${:,.2f}".format(self.account_number,self.balance))

11

Now, if we try to create an object of BankAccount, we will need to pass two arguments.

(The following code block demonstrates the error if we do not.)

1account = BankAccount() # Raises a type error

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[10], line 1

----> 1 account = BankAccount() # Raises a type error

TypeError: BankAccount.__init__() missing 2 required positional arguments: 'account_number' and 'customer_id'

1account = BankAccount(5345239,1223)

2account.show_information()

Account #5345239: $0.00

The revised class definition of BankAccount shows several concepts:

First, we assigned a class attribute balance to BankAccount. Any created objects will automatically contain these class attributes with the currently assigned value. We can use a class attribute as a default value. Other uses of class attributes include storing class constants (e.g., the value of pi in a math class), and tracking data across all the instances (number of objects created, list of objects created, etc.) While not a recommended practice, programmers can also add attributes to a class after it has been defined1.

Second, we added an initializer method2 __init__(). Within Python, we use initializer methods to establish a new object’s state properly. As a general rule, an “initialized” object should be in a “good” state such that objects can use it.

This initializer defines two object attributes(state): account_number and customer_id.

One of the odd things to highlight with the initializer method is the first parameter, self. Due to the design of the Python language, the first parameter to any object’s method must be a reference to the object itself. By convention, programmers use the name self for this reference3. It is impossible to pass this argument explicitly - Python automatically supplies the reference to methods when the methods are defined as part of a class and using the object.method() call syntax4.

Finally, we define another method, show_information(), that prints an object’s account number and current balance.

With a statement such as account = BankAccount(5345239,1223), a series of actions occurs:

The Python interpreter

looks up the definition of the

BankAccountclass;creates a new object;

calls the new object’s

__init__()method passing two arguments;stores the values for account_number and customer_id in the object (i.e., they are now attributes of the object);

returns the new object’; and

assigns the reference of the new object to the variable

account.

28.3. Attributes#

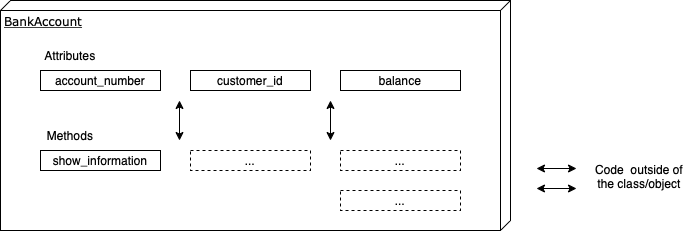

Attributes are fundamental to object-oriented programming. By defining attributes, we encapsulate that data and the code that operates upon that data into a single object.

Typically in object-oriented programming, we also use information hiding - an object’s ability to hide its implementation details from code outside the object. As the above diagram shows, external code should indirectly access the object’s state by calling the object’s methods.

By hiding these data attributes(state), we gain a number of advantages:

It simplifies the ability for external code/objects to work with the object as they don’t need to understand the implementation details.

The implementation details can be changed within the class and not affect external code.

Protect attributes protected against accidental changes and corruption.

Can validate changes to attributes. For example, should a negative balance be allowed? What should occur if the balance becomes negative?

28.3.1. Direct Access#

Unfortunately, Python does not strictly enforce information hiding. Other languages define accessibility modifiers to attributes and methods which limit what other objects can directly access those methods. With the above definition of BankAccount, you can get and set attribute values directly:

1account = BankAccount(5345239,1223)

2print("Account Number:", account.account_number)

3print("Customer:", account.customer_id)

4print("Balance:", account.balance)

5account.balance = -10000 ## uh, oh ..

6print("Balance:", account.balance)

Account Number: 5345239

Customer: 1223

Balance: 0.0

Balance: -10000

28.3.2. Properties: Getters & Setters#

While programmers can use obfuscated names (e.g., adding a prefix like ‘hidden_’) to identify that other objects should not directly use an attribute, the Pythonic solution is to use properties.

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 hidden_balance = 0.0 # must change name otherwise a recursive overflow error occurs

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id):

6 self.hidden_account_number = account_number

7 self.hidden_customer_id = customer_id

8

9 def show_information(self):

10 print("Account #{:d}: ${:,.2f}".format(self.hidden_account_number,self.hidden_balance))

11

12 def get_balance(self):

13 return self.hidden_balance

14

15 def set_balance(self, new_balance):

16 self.hidden_balance = new_balance

17

18 # Establishes ability to directly access "balance" to get a value and set a new value

19 balance = property(get_balance,set_balance)

20

21 # Note: not defining attributes for account_number and customer_id to save space

1b = BankAccount(12,2)

2b.balance = 100.0

3print(b.balance)

100.0

We can also use decorators (discussed in a later notebook) rather than calling property() directly.

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 hidden_balance = 0.0 # must change name otherwise a recursive overflow error occurs

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id):

6 self.hidden_account_number = account_number

7 self.hidden_customer_id = customer_id

8

9 def show_information(self):

10 print("Account #{:d}: ${:,.2f}".format(self.hidden_account_number,self.hidden_balance))

11

12 @property

13 def balance(self):

14 return self.hidden_balance

15

16 @balance.setter

17 def balance(self, new_balance):

18 self.hidden_balance = new_balance

1b = BankAccount(12,2)

2b.balance = 100.0

3print(b.balance)

100.0

As an exercise, you may want to add print statements to the methods to see that they are called - or step through the code with a debugger.

You can also use these decorators to create properties for computed values.

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 hidden_balance = 0.0 # must change name otherwise a recursive overflow error occurs

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id):

6 self.hidden_account_number = account_number

7 self.hidden_customer_id = customer_id

8

9 def show_information(self):

10 print("Account #{:d}: ${:,.2f}".format(self.hidden_account_number,self.hidden_balance))

11

12 @property

13 def balance(self):

14 return self.hidden_balance

15

16 @balance.setter

17 def balance(self, new_balance):

18 self.hidden_balance = new_balance

19

20 @property

21 def is_overdrafted(self):

22 return self.hidden_balance < 0;

1b = BankAccount(12,2)

2b.balance = -100.0

3print(b.balance)

4print(b.is_overdrafted)

-100.0

True

As is_overdrafted does not have a setter, you can not set the value from outside of the object - this is a convenient mechanism for read-only attributes.

28.3.3. Name Mangling#

Python implements a naming convention for attributes that should be private by beginning those attributes with two underscores __. Note: this naming convention does not make the attribute completely private - Python mangles the attribute name to make it a conscious act to access the attribute directly5.

While more of a topic for the next notebook, name mangling also reduces the risk of name clashes in subclasses. Imagine you have a base class with an attribute or method meant to be used only internally within that class. If a subclass accidentally defines an attribute or method with the same name, it would unintentionally override the one in the base class.

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 __balance = 0.0 # must change name otherwise a recursive overflow error occurs

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id):

6 self.__account_number = account_number

7 self.__customer_id = customer_id

8

9 def show_information(self):

10 print("Account #{:d}: ${:,.2f}".format(self.__account_number,self.__balance))

11

12 @property

13 def balance(self):

14 return self.__balance

15

16 @balance.setter

17 def balance(self, new_balance):

18 self.__balance = new_balance

19

20 @property

21 def is_overdrafted(self):

22 return self.__balance < 0;

1b = BankAccount(12,2)

2b.balance = -100.0

3print(b.balance)

4print(b.is_overdrafted)

5

6print(b._BankAccount__balance) #mangled name. Python adds _ClassName as a prefix

7print(b.__balance) #will cause an Attribute error

-100.0

True

-100.0

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[20], line 7

4 print(b.is_overdrafted)

6 print(b._BankAccount__balance) #mangled name. Python adds _ClassName as a prefix

----> 7 print(b.__balance) #will cause an Attribute error

AttributeError: 'BankAccount' object has no attribute '__balance'

28.4. Methods#

Python contains several different method types related to classes.

28.4.1. Instance Methods#

If a decorator (@staticmethod or @classmethod) does not exist, then the method is an instance method. Every method shown so far has been of this type. Usually, the first parameter of instance methods is named self. When calling the method, Python automatically passes that reference (to the object itself). While you will not receive an error message when you define a method without the “self” parameter, a runtime error will occur when you try to call the method

1class Test:

2 def method():

3 return "test"

4a=Test()

5a.method() # causes runtime erorr. How do you fix this? Correct the code and re-run

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[21], line 5

3 return "test"

4 a=Test()

----> 5 a.method() # causes runtime erorr. How do you fix this? Correct the code and re-run

TypeError: Test.method() takes 0 positional arguments but 1 was given

28.4.2. Class Methods#

In contrast to instance methods, class methods are called against the class as a whole and are used to access or modify any class state.

To create a class method, we must explicitly use the @classmethod decorator; otherwise, Python will treat it as an instance method.

1class Student:

2 school_name = "Acme University"

3

4 def __init__(self,name,student_id):

5 self.__name = name

6 self.__student_id = student_id

7

8 @classmethod

9 def update_school(cls,name):

10 cls.school_name = name # can also use Student.school_name = name

1a = Student('John',1)

2print(a.school_name)

3b = Student('Steve',2)

4b.school_name = 'Greeks R Us'

5Student.update_school('The University of Acme')

6print(a.school_name)

7print(b.school_name)

Acme University

The University of Acme

Greeks R Us

Notice that the class attribute change in line 5 affected ‘a’ but not ‘b’. So changing the class value will not be seen in objects where we have already changed that attribute. The following code block demonstrates this as well.

1class A:

2 count = 0

3 def __init__(self):

4 A.count += 1

5 @classmethod

6 def show_count(cls):

7 print("Created {:d} objects of this type".format(cls.count))

8x = A()

9y = A()

10y.count = 0

11z = A()

12A.show_count()

13print("x:",x.count)

14print("y:",y.count)

15print("z:",z.count)

Created 3 objects of this type

x: 3

y: 0

z: 3

28.4.3. Static Methods#

Static methods are commonly utility methods that perform a related task to the class but do not access class or instance attributes. i.e., Static methods perform their work in isolation. To declare a static method, use the @staticmethod decorator without any self or cls parameter. If we need to reference one of those parameters, we should define an instance or a class method.

1class School:

2 @staticmethod

3 def show_tagline():

4 print("Acme University is where your dreams come true...")

5School.show_tagline()

Acme University is where your dreams come true...

28.4.4. Magic Methods#

Also referred to as dunder (double underscore) methods, Python defines special methods that start and end with double underscores to provide additional capabilities to objects.

In this notebook, we have used one such method __init__ to initialize newly created objects. Behind the scenes, the Python interpreter automatically calls this method. We have also indirectly used these magic methods by calling built-in functions and comparison operators. Behind the scenes, the Python interpreter calls the appropriate magic method, such as __eq__ for the equality operator. As another example, the with statement automatically calls __enter__ and __exit__.

As necessary, implement these methods in your code.

The Python documentation has a page for special method names. Rafe Kettler has also written an in-depth guide on magic methods

Three specific magic methods to implement:

28.4.4.1. __str__#

__str__ is a magic method that defines the behavior when the str() method is called with your object to convert it to a human-readable string representation.

28.4.4.2. __repr__#

From the Python documentation -

Called by the repr() built-in function to compute the “official” string representation of an object. If at all possible, this should look like a valid Python expression that could be used to recreate an object with the same value (given an appropriate environment). If this is not possible, a string of the form <…some useful description…> should be returned. The return value must be a string object. If a class defines __repr__() but not __str__(), then __repr__() is also used when an “informal” string representation of instances of that class is required.

This is typically used for debugging, so it is important that the representation is information-rich and unambiguous.

28.4.4.3. __eq__#

__eq__ is a magic method that defines the behavior when the == operator is used just after your object. This method will take two parameters: self and other - the object on the right side of the operator. Within this method, you should first check that the objects are of the same type, then validate that the relevant state is equivalent. If the objects are not of equivalent type, you should return NotImplemented in Python (discussed below).

28.4.4.4. Magic Methods in BankAccount#

The BankAccount class with these three methods defined: (show_information removed as __str__ provides the same functionality.)

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 __balance = 0.0 # must change name otherwise a recursive overflow error occurs

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id):

6 self.__account_number = account_number

7 self.__customer_id = customer_id

8

9 def __str__(self):

10 return "Bank Account #{:d}, Customer: {:d}, ${:,.2f}".format(self.__account_number,

11 self.__customer_id,

12 self.__balance)

13

14 def __repr__(self):

15 return str(self.__dict__)

16

17 def __eq__(self, other):

18 if not isinstance(other,BankAccount):

19 return NotImplemented # Notice this return value, discussed below

20

21 return self.__account_number == other.__account_number and \

22 self.__customer_id == other.__customer_id

23

24 @property

25 def balance(self):

26 return self.__balance

27

28 @balance.setter

29 def balance(self, new_balance):

30 self.__balance = new_balance

31

32 @property

33 def is_overdrafted(self):

34 return self.__balance < 0;

35

1account = BankAccount(99874,223)

2print(account) # __str__ is implicitly called

3account # the jupyter environment returns the __repr__ value here

4

5account2 = BankAccount(123455, 223)

6account3 = BankAccount(99874,223)

7print("Equality between account and acount2:", account == account2)

8print("Equality between account and acount3:", account == account3)

Bank Account #99874, Customer: 223, $0.00

Equality between account and acount2: False

Equality between account and acount3: True

In Python, NotImplemented is a special singleton value (not the same as an exception like NotImplementedError) that can be returned from certain special methods, like the rich comparison methods (__eq__, __lt__, __le__, etc.) or arithmetic methods (__add__, __mul__, etc.). Returning NotImplemented indicates that the operation is not implemented for the provided operands.

The primary purpose of returning NotImplemented instead of raising an error or returning False is to allow Python to try alternative operations or reflect the operation to the other operand. This provides a way to support operations between instances of different classes in a cooperative and extensible way. Further details

28.4.5. Method Overloading#

Unlike many other languages, Python does not support method overloading - the ability to define multiple methods with the same name but different parameters.

As soon as the second method with the first name is defined, the Python interpreter overwrites the namespace dictionary with the new method definition.

While this seems to be a significant shortcoming, Python’s flexibility with default parameters and the ability to pass a variable number of arguments with the *args parameter reduce the need for the capability.

Proper method overloading requires the language to be able to discriminate between types both at compile-time and runtime. As a dynamically typed language, Python does not directly have this capability. With Python, though, we can provide a similar capability if the need arises through a “multiple dispatch” technique. With this approach, the interpreter differentiates among multiple methods at runtime based on the current argument types.

Martin Heinz provides a good explanation on his blog. [PDF version]

28.4.6. Method Name Mangling#

As with attribute names, method names can also be mangled to indicate to other programmers that they are meant for internal use within the class.

1class MangledDemo:

2 def __mangle(self):

3 return "mangled!"

4a=MangledDemo()

5a._MangledDemo__mangle()

'mangled!'

28.5. Naming Conventions#

Python employs several naming conventions to help guide programmers in creating method and attribute names:

From Python naming conventions

In addition, the following special forms using leading or trailing underscores are recognized (these can generally be combined with any case convention):

_single_leading_underscore: weak “internal use” indicator. E.g. from M import * does not import objects whose name starts with an underscore.

single_trailing_underscore_: used by convention to avoid conflicts with a Python keyword, e.g., Tkinter.Toplevel(master, class_=’ClassName’)

__double_leading_underscore: when naming attributes or methods, invokes name mangling (inside class FooBar, __boo becomes _FooBar__boo; see below).

__double_leading_and_trailing_underscore__: “magic” objects or attributes that live in user-controlled namespaces. E.g. __init__, __import__ or __file__. Never invent such names; only use them as documented.

28.6. Terminology Review#

A class is a set of objects that share the same set of attributes (the names and types, not necessarily values) and common behavior. More practically, we can view a class as the code that specifies the attributes and methods for this set of objects. A class serves as a blueprint when creating objects. Programmers can use the terms class, type, and data type interchangeably.

An object is an instance of a class that contains attributes (state) and methods (behavior). State, attribute, and property are used interchangeably. An object’s members consist of both the attributes and the methods.

Functions and methods are largely the same. However, methods must be declared within the context of a class. Functions can be accessed independent of an object. Methods require an object or class reference. Routine may refer to functions or methods.

A message is simply a method call on an object. This historical usage has declined over the past twenty years due to the emergence of distributed systems and the application of that term (message) to send information back and forth among independent processes.

28.7. Object Life Cycle#

An object’s life cycle proceeds through three phases: creation, handling, and destruction.

In creation, Python splits this into two distinct magic methods: __new__ to allocate the object and then __init__ to initialize the object. In most situations, you will only need to implement __init__.

Handling simply means using the object in your program: setting attributes, reading attributes, calling methods on the object, etc.

Destruction occurs when the object can no longer be referenced. The Python interpreter at some point (no guarantees exist on if or when) will call the __del__ method on the object and then free any allocated memory. If you need to reclaim or otherwise handle any resources (besides memory which automatically occurs), you should explicitly perform these actions when appropriate in the program - do not rely upon overriding __del__ and having the interpreter call that method.

Garbage collection is the process of removing objects when they can no longer be referenced - this includes calling any __del__ methods and freeing allocated memory.

28.8. Class Invariants#

Invariants are a set of conditions(assumptions) that must always hold true during the life of a program (or, more narrowly, by the life of an object). You can consider this to be a combined precondition and postcondition - it must be valid before and after a call to a method. However, while executing a routine that changes the relevant state/attributes for the condition, the invariant may not necessarily be true. Invariants should hold during the object’s lifetime - from the end of its constructor to the end of its destructor. As an example, the radius of a circle must always be nonnegative. We also apply the term invariant to a sequence of operations. In this user, the invariant is the set of conditions that remain true during these operations.

For example:

1class Circle:

2 def __init__(self, radius):

3 if radius < 0:

4 raise ValueError("Radius cannot be a negative number")

5 self.__radius = radius

6

7 def compute_circumference(self):

8 assert self.__radius >= 0, "Discovered negative radius"

9 return 2 * self.__radius * 3.14159

At first glance, the assert in compute_circumference does not seem necessary. However, a programmer could have manually changed a circle’s radius after the circle’s construction.

1a = Circle(2.5)

2a._Circle__radius = -1.0

3a.compute_circumference() # causes an AssertionError

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AssertionError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[30], line 3

1 a = Circle(2.5)

2 a._Circle__radius = -1.0

----> 3 a.compute_circumference() # causes an AssertionError

Cell In[29], line 8, in Circle.compute_circumference(self)

7 def compute_circumference(self):

----> 8 assert self.__radius >= 0, "Discovered negative radius"

9 return 2 * self.__radius * 3.14159

AssertionError: Discovered negative radius

Or, in another situation, suppose a coworker changed the Circle class to add a method that allows a correction percentage that would modify a radius. That correction percentage could be positive or negative. The initial implementation could have been -

1class Circle:

2 def __init__(self, radius):

3 if radius < 0:

4 raise ValueError("Radius cannot be a negative number")

5 self.__radius = radius

6

7 def compute_circumference(self):

8 assert self.__radius >= 0, "Discovered negative radius"

9 return 2 * self.__radius * 3.14159

10

11 def apply_correction(self, percent_change):

12 self.__radius *= percent_change

1a = Circle(2.5)

2a.apply_correction(-.01)

3a.compute_circumference()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AssertionError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[32], line 3

1 a = Circle(2.5)

2 a.apply_correction(-.01)

----> 3 a.compute_circumference()

Cell In[31], line 8, in Circle.compute_circumference(self)

7 def compute_circumference(self):

----> 8 assert self.__radius >= 0, "Discovered negative radius"

9 return 2 * self.__radius * 3.14159

AssertionError: Discovered negative radius

The coworker had not fully considered the potential side issues the change may have. While this is relatively simple, similar problems occur in much more complex situations. Using the assert, we at least have a sanity check. Our testing may or may not have found this particular situation.

In looking at the Circle class, we applied name mangling to highlight that developers should not directly change the values. However, we can create a more robust situation by validating the radius whenever it is changed. In this solution, we establish a getter and setter property for radius. The radius setter always validates that its value is nonnegative. Notice that in the following code, __init__ calls the radius setter to perform validation. If __init__ simply tried to assign directly to self.__radius, the validation would be skipped. Notice, that the input validation occurs before assigning the value to an object’s state - we do not want to put an object into an invalid state.

1class Circle:

2 def __init__(self, radius):

3 self.radius = radius

4

5 @property

6 def radius(self):

7 return self.__radius

8

9 @radius.setter

10 def radius(self, radius):

11 if radius < 0:

12 raise ValueError("Radius cannot be a negative number")

13 self.__radius = radius

14

15 def compute_circumference(self):

16 assert self.radius >= 0, "Discovered negative radius"

17 return 2 * self.radius * 3.14159

18

19 def apply_correction(self, percent_change):

20 self.radius *= percent_change

1a = Circle(-3) # raises a ValueError

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[34], line 1

----> 1 a = Circle(-3) # raises a ValueError

Cell In[33], line 3, in Circle.__init__(self, radius)

2 def __init__(self, radius):

----> 3 self.radius = radius

Cell In[33], line 12, in Circle.radius(self, radius)

9 @radius.setter

10 def radius(self, radius):

11 if radius < 0:

---> 12 raise ValueError("Radius cannot be a negative number")

13 self.__radius = radius

ValueError: Radius cannot be a negative number

1b = Circle(3)

2b.apply_correction (-1.01) # raises a ValueError

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[35], line 2

1 b = Circle(3)

----> 2 b.apply_correction (-1.01) # raises a ValueError

Cell In[33], line 20, in Circle.apply_correction(self, percent_change)

19 def apply_correction(self, percent_change):

---> 20 self.radius *= percent_change

Cell In[33], line 12, in Circle.radius(self, radius)

9 @radius.setter

10 def radius(self, radius):

11 if radius < 0:

---> 12 raise ValueError("Radius cannot be a negative number")

13 self.__radius = radius

ValueError: Radius cannot be a negative number

28.9. Bank Account and Transactions#

In this section, we present another version of the BankAccount class, but this time we track the transactions that occur against the account.

We first define a Transaction class that can track debits/credits against an account. Specifically, objects of this class contain an ID, a description, an amount, and a timestamp when we registered the transaction.

We then provide a new class for BankAccount. We provide an initial balance as an attribute, but no longer allow the setting of that attribute directly. The BankAccount can now process transactions. In this method, we check that the type is actually of Transaction. Then, we alter the balance based on the transaction amount. We also add the transaction to a list of transactions we maintain for the accounts. Finally, we allow users of the BankAccount class to get a read-only view of that list by returning a tuple of the processed transactions.

In this example, we demonstrate an object-oriented principle called aggregation in which one object contains (possesses) one or more instances of another type of object. In aggregation, the different types of objects can exist independently. While it may not be true in a system, in this example, we allow a Transaction to exist independent of a BankAccount.

1import datetime as dt

2

3class Transaction:

4 """Simple transaction method track a change to an account"""

5 __id = 100

6

7 def __init__(self, description, amount):

8 self.__id = Transaction.__id

9 Transaction.__id += 1

10

11 self.__description = description

12 self.__amount = amount

13 self.__timestamp = dt.datetime.now(dt.timezone.utc)

14

15 def __str__(self):

16 return "Transaction #{:d} - {:s} - {:s}, ${:,.2f}".format(self.__id, self.__timestamp.isoformat()[0:19],

17 self.__description, self.__amount)

18

19 def __repr__(self):

20 return str(self.__dict__)

21

22 @property

23 def id(self):

24 return self.__id

25

26 @property

27 def description(self):

28 return self.__description

29

30 @property

31 def amount(self):

32 return self.__amount

33

34 @property

35 def timestamp(self):

36 return self.__timestamp

1class BankAccount:

2 """Bank Account represents different accounts a customer may have within the system."""

3 __balance = 0.0 # must change name otherwise a recursive overflow error occurs

4

5 def __init__(self, account_number, customer_id, balance):

6 self.__account_number = account_number

7 self.__customer_id = customer_id

8 self.__transactions = []

9 self.__balance = balance

10

11 def __str__(self):

12 return "Bank Account #{:d}, Customer: {:d}, ${:,.2f}".format(self.__account_number,

13 self.__customer_id,

14 self.__balance)

15

16 def __repr__(self):

17 return str(self.__dict__)

18

19 @property

20 def balance(self):

21 return self.__balance

22

23 @property

24 def is_overdrafted(self):

25 return self.__balance < 0;

26

27 @property

28 def transactions(self):

29 return tuple(self.__transactions)

30

31 def process_transaction(self, trans):

32 if not isinstance(trans,Transaction):

33 raise ValueError("not a Transaction object")

34 self.__balance += trans.amount

35 self.__transactions.append(trans)

1my_account = BankAccount(45223,124232,10000)

2print(my_account)

3bb = Transaction("Best Buy", -245.34)

4print(bb)

5my_account.process_transaction(bb)

6my_account.process_transaction(Transaction("Food World", -145.96))

7my_account.process_transaction(Transaction("University Paycheck", 1204.50))

8print(my_account)

9transactions = my_account.transactions

10for t in transactions:

11 print(t)

Bank Account #45223, Customer: 124232, $10,000.00

Transaction #100 - 2024-04-29T01:45:44 - Best Buy, $-245.34

Bank Account #45223, Customer: 124232, $10,813.20

Transaction #100 - 2024-04-29T01:45:44 - Best Buy, $-245.34

Transaction #101 - 2024-04-29T01:45:44 - Food World, $-145.96

Transaction #102 - 2024-04-29T01:45:44 - University Paycheck, $1,204.50

28.10. Discussion#

So why do I need objects when I have lists, dictionaries, and functions? Technically, you do not. But how do you prevent yourself or others from making mistakes? What if you were tracking stocks, and somehow the price became negative? Is someone giving away shares? Using an initializer or property setter can help prevent such mistakes.

A future notebook will cover object-oriented principles and design approaches in more detail.

28.11. Suggested LLM Prompts#

Explain the core concepts of object-oriented programming (OOP), including objects, classes, encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism. Define what a class is in Python and how it serves as a blueprint for creating objects. Demonstrate creating a simple class and instantiating an object from it.

Explain how attributes represent the state of an object, and methods represent its behavior. Demonstrate how to define class attributes and instance attributes, and how to create methods that access and modify these attributes. Include examples of both instance methods and class methods.

Explain the purpose of the

__init__method in Python classes, which is the constructor used for initializing objects. Demonstrate how to define the__init__method and how to pass arguments to it when creating an object. Show examples of initializing object attributes with different data types.Explain the concept of encapsulation in OOP, which is the bundling of data and methods into a single unit. While Python does not have access modifiers similar to other languages such as C++ and Java, demonstrate the common conventions used in Python to control the visibility and accessibility of object members. Show examples of how to access and modify private attributes using @property and @settter decorators

Explain the difference between instance methods, class methods, and static methods in Python. Demonstrate how to define and use class methods and static methods, and provide examples of when each type of method would be appropriate.

Explain the concepts of composition and aggregation in OOP, which are ways of combining objects or classes. Demonstrate how to create objects that are composed of or aggregated from other objects. Show examples of how composition and aggregation can be used to build more complex systems.

Introduce some common design patterns in OOP, such as the Singleton pattern, Factory pattern, or Observer pattern. Explain how these patterns can be implemented in Python using classes and objects. Discuss best practices for writing clean, maintainable, and extensible code using OOP principles.

Explain garbage collection in Python.

28.12. Review Questions#

What is a class in Python, and what is its purpose?

How do you define a class in Python?

What is an object in Python, and how is it related to a class? Explain how an object has state, behavior, and an identity.

How do you create an instance of a class (an object)?

What is the purpose of the

__init__method in a Python class?How do you define instance attributes in a class?

What is the difference between instance attributes and class attributes?

How do you define methods in a Python class? What is the purpose of the self parameter in Python class methods?

How do you access and modify instance attributes from within a class method?

What are class methods in Python, and how do they differ from instance methods?

What are static methods in Python, and when would you use them?

What is encapsulation in object-oriented programming, and how is it achieved in Python?

How do you define and use getters and setters in Python classes? Focus on the appropriate decorators.

Explain how it is not possible in Python to prevent code outside the class definition from directly accessing attributes. How do programmers signify to avoid doing this, though?

What name pattern is used in Python to override various operators such as

==and<? What are these methods called?What will be the output of the following Python code:

class test: def __init__(self,a="Hello World"): self.a=a def display(): print(self.a) obj=test() obj.display()

- The program has an error because constructor can’t have default arguments

- Nothing is displayed

- “Hello World” is displayed

- The program contains an error and a stack trace appears

What does built-in function

type()do in the context of classes?How do you create an empty class in Python? Why is creating an empty class useful?

What is the output of the following code?

class demo(): def __repr__(self): return '__repr__ built-in function called' def __str__(self): return '__str__ built-in function called' s=demo() print(s)

- __str__ built-in function called

- __repr__ built-in function called

- An exception occurs as demo does not have an __init__ method

- Nothing is printed.

What is the

__del__method used for in Python? Explain when it is invoked. Can programmers rely upon it being invoked?

28.13. Exercises#

Implement a class to model a book in this exercise. The class

Bookhas the properties: name, authors, publisher, list_price, num_units_sold, and total_salesfowler_book = Book("Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code",["Martin Fowler"], "Addison Wesley", 39.95, 4_023_342, 120_000_000.00) gof_book = Book("Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software", ["Erich Gamma","Richard Helm","Ralph Johnson","John Vlissides"], "Addison Wesley", 45.95, 5_123_423, 224_234_954.00) c_book = Book("The C Programming Language", ["Brian W. Kernighan", "Dennis M. Ritchie"], "Prentice Hall", 60.30, 9_343_123, 433_231_924.00)

Define the class Book with an initializer to store the 6 defined properties.. Property names should start with

__. You should use the decorator for properties (@property and @name.setter) in methods to get and set data. The only attributes that need setters are forlist_price,num_units_soldandtotal_sales.Create dunder methods to override eq, ge, gt,le,lt. Use the comparison of the name for these methods

Define a __str__ method to produce a bibliographic reference.

Create a __repr__ method that prints out the attributes as a dictionary literal.

Create a property method that computes the average unit sold price

Define a class Bookshelf that holds a collection of books. Implement the following behavior:

add_book(book). Adds a book to the bookshelf

remove_book_by_title(title). Removes a book based upon its title.

find_most_expensive_book(). Returns the most expensive book.

Implement a class named

MyClock24that represents a 24-hour hour clock. Objects of this class should have three instance properties: hour, minute, and second. (Note: this does not require that you have to track the clock state with three variables, only that you have to expose / implement those three properties to get and set the time. Using the information hiding principle, a class should decide its implementation. ) The following behavior needs to be implemented:an initializer that has three parameters: hours, minutes, and seconds

a

tick()method that advances the clock one second.a __str__ method that prints the time in this format: HH:MM:SS

a __repr__ method that prints out the hour, minute, and second attributes as a dictionary literal.

Override the dunder methods for eq, ne, ge, gt,le,lt. Use the comparison of the full time for these methods.

Override the dunder methods for add, sub to add and substract times. You either accept another MyClock24 object as the second parameter an int that represents the number of ticks to move the clock forward or back.

Note: If the time goes outside of the range of 00:00:00 to 23:59:59, then the time should roll over / roll back as appropriate.

28.14. Notes#

This is another example of Python expecting programmers to play nice together/be “fully grown adults”. For example, we can add a new class attribute to BankAcount to track sign-up bonuses. Any new objects instantiated from BankAccount will now have this attribute, while existing objects will not.

BankAccount.signup_bonus = 50.0

new_account = BankAccount(32315,543)

print("new account", new_account.signup_bonus)

print("account", account.signup_bonus)

From a code maintenance perspective, tracking such ad-hoc attribute additions and changes becomes difficult. Additionally, the value of these class attributes can be changed. The class and any new objects will see the new value, while existing objects will be unchanged.

Within Python, two steps are necessary to create an object:

Create a new, uninitialized object.

Initialize the object for use.

Python performs these two steps with

__new__and__init__, respectively. Generally, you will not need to implement__new__. Other object-oriented languages, such as C++ and Java, combine these two steps into one with a constructor.Continue to use the name

selffor this purpose; other programmers will expect this convention. Using a different name, while legal, will confuse those who have to maintain your code. This may even be you, many months or years later. Other programming languages such as C++ and Java use the keywordthisand implicitly make the self-reference available.It is possible to explicitly pass the object reference when we use the class as part of the method call:

BankAccount.show_information(account) Account #5345239: $0.00

This behavior demonstrates some of the inner workings of Python and how the language evolved.

account.show_information()is a shortcut for the code above. Removing this behavior would be a difficult undertaking as any Python code using classes would be affected.Again, another example of playing nice together. The mungling pattern

_ClassName__AttributeNameis well known, and the updated names can still be easily discovered withdir()