19. C++ Standard Library#

While we have made extensive use of C++’s Standard Library, we have not discussed the components:

C++ Standard library

C++ Input/Output Stream Library: std::cin, std::cout, ifstream, ofstream, etc.

C++’s Miscellaneous Library: strings, exceptions, localization, …

C++’s Standard Template Library(STL): Containers, Iterators, and Algorithms

The C++ Standard Template Library (STL) is an influential part of the C++ Standard Library that provides data structures, algorithms, and iterators. The primary impetus for the STL came from Alexander Stepanov who had been developing the concept of generic programming since the late 1970s. His goal was to have an efficient and abstract way to work with sequences of data without being tied down to specific data structures. The ideas behind the STL have influenced many other programming languages and libraries. Its emphasis on algorithmic design, generic programming, and data structure abstraction has become a standard in modern software design.

19.1. STL Containers#

A container is an object that stores a collection of other objects/elements.

Within C++, containers are primary divided into two categories: sequential and associative. Sequential containers are similar to Python’s lists while associative containers mirror Python’s dictionaries and sets.

Sequential Container Type |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Flexible-sized array. Supports fast random access. Inserting/deleting elements at other points than the end of the collection may be slow as the library uses arrays to hold the elements - inserts at other than the end require data elements to be moved. |

|

Double-ended queue. Support fast random access as well as fast insert/delete operations at both the front (beginning) or the back (end) of the collection |

|

doubly-linked list. Supports only bidirectional sequential access. |

|

Single lined list. Can only perform access in one direction. |

|

Fixed-sized array |

|

Specialized container that contains sequences of characters. (Technically, it is not part of the STL, but does have most of the functionality of STL containers.) |

With the exception of the array, these containers provide efficient and flexible in-memory stores. We can grow the sizes as needed. As strings and vectors hold elements in contiguous memory, we have the same advantages of built-in arrays, but without the hassle of memory management.

Note that these containers do store by value (and not by reference).

//filename: vector.cpp

//complile: g++ -std=c++17 -o vector vector.cpp

//execute: ./vector

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

vector<double> numbers;

string line;

cout << "Type some numbers to average Hit ctrl-d when you are complete." << endl;

while (getline(cin,line)) {

try {

double d = std::stod(line);

numbers.push_back(d);

} catch (const std::invalid_argument&) {

cerr << "Invalid argument: " << line << endl;

} catch (const std::out_of_range&) {

cerr << "out of range of double: " << line << endl;

}

}

double total = 0.0;

for (int i=0; i < numbers.size(); i++) {

total += numbers[i];

}

cout << "Average: " << total/numbers.size() << endl;

cout << "Number of elements: " << numbers.size() << endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Some rules of thumb in deciding which contain to use: (C++ Primer, 5th Ed, Lippman et al)

Unless you have a reason to use another container, use a

vector.If your program has lots of small elements and space overhead matters, don’t use use list or forward list

If the program requires random access (selecting any arbitrary index), use a vector or dequeue.

if the program needs to insert or delete elements in the middle of the container, use a list or forward list

If the program needs to insert or delete elements at the front and the back, but not in the middle, use a deque.

If you are not sure which container to use, write the code so that is uses operations in common with both vectors and lists. Use iterators to access data. This strategy will allow you to change the underlying container type in the future depending upon write and access patterns..

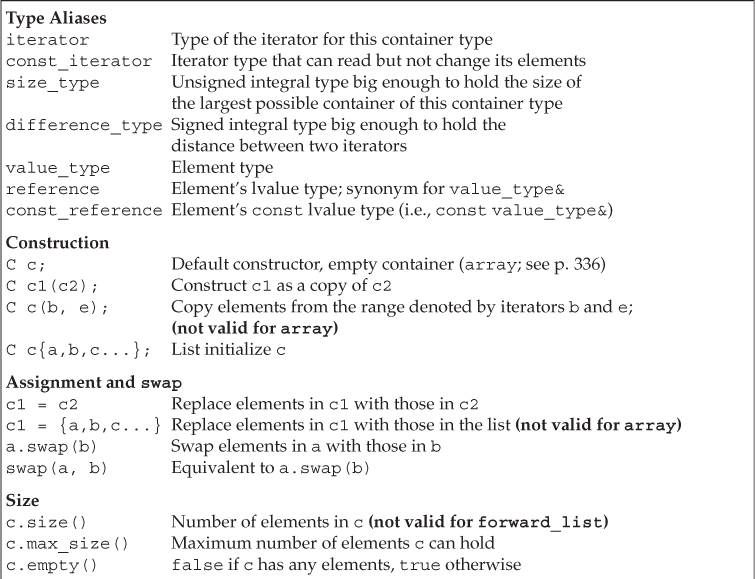

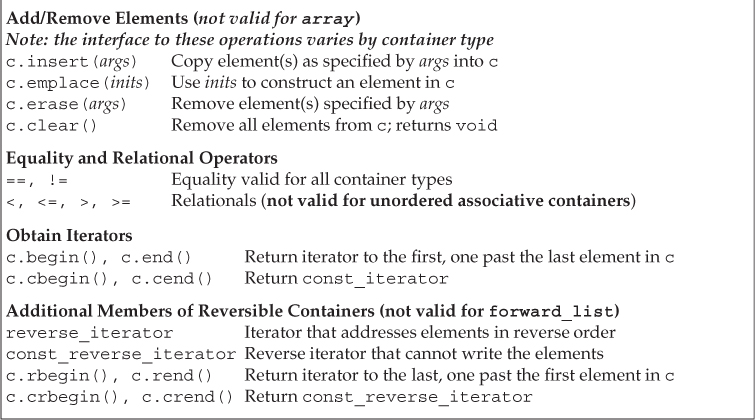

The following images (taken from the C++ Primary) show the operations provided by all of the container types:

19.2. STL Iterators#

Each container class has an associated iterator class (e.g. vector<int>::iterator) used to iterate through elements of the container. The iterator range for a container is actually denoter by a pair of iterators, each of refer to an element (or for the end, one past the last element) in the container. The range is from the beginning (inclusive) up until the end (exclusive). Mathematically, this is typically denoted as [begin, end) and is often called a left-inclusive interval.

Left-inclusive ranges have three properties that affect programming:

If

beginequalsend, the range is empty.If

beginis not equal toend, at least one element exists in the range;beginrefers to the first element in that range.begincan be incremented some number of times untilbegin == end.

With these properties, we can now safely write loops to process a range of elements:

while (begin != end) {

*begin = val; // access begin - dereference to assign or access the value

begin++; // move to the next element

}

These iterators are necessary as the different containers store their elements differently - not every container can easily be accessed with the index [] operator as with arrays and vectors. Thus, they provide an abstraction with a common interface/pattern to access the various elements. In the following example, notice how we combine generic programming and the properties underlying left-inclusive ranges in the print() function.

//filename: script1.cpp

//complile: g++ -std=c++17 -o script1 script1.cpp

//execute: ./script1

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

template <typename T>

void print(T begin, T end) {

while (begin != end) {

cout << *begin << "\n";

begin++;

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

vector<string> lines;

lines.push_back("It was the best of times.");

lines.push_back("It was the worst of times.");

lines.push_back("It was the age of wisdom");

lines.push_back("It was the age of foolishness");

for (vector<string>::iterator it = lines.begin(); // lines.begin() marks the start of the container range

it < lines.end(); // lines.end() marks one past the end of the container range

it++ ) {

cout << *it << endl;

}

cout << "\nNow, repeat, but using a generic function and the iterator range\n";

print(lines.begin(),lines.end());

cout << "\n\nNow in reverse:\n";

for (auto it = lines.rbegin(); it < lines.rend(); it++ ) { //loop backwards, use auto for the variable type

cout << *it << endl;

}

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Some container iterators support more operations than others:

All can be incremented (

++), copied, copy-constructedSome can be dereferenced on RHS (e.g.

x = *it;)Some can be dereferenced on LHS (e.g.

*it = x;)Some can be decremented (

--)Some support random access ([], +, -, +=, -=, <, > operators)

With C++11, we can use the auto keyword to infer types. This simplifies declaring more complicated return types:

auto index = lines.begin(); // auto fills in "vector<string>::iterator" from the prior example

C++11 has also added a for-each loop. The declaration defines a loop variable and the expression is an object that is some sort of a sequence.

for (declaration: expression) {

//statements

}

//filename: lineforeach.cpp

//complile: g++ -std=c++17 -o lineforeach lineforeach.cpp

//execute: ./lineforeach

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

vector<string> lines;

lines.push_back("It was the best of times.");

lines.push_back("It was the worst of times.");

lines.push_back("It was the age of wisdom");

lines.push_back("It was the age of foolishness");

for (auto line: lines) {

cout << line << endl;

}

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

19.2.1. Iterator Ranges and Pointers#

Not by chance, these same basic properties of iterator ranges apply to pointers and access contiguous memory addresses in an array. Consider the following code -

char str[] = "Hello"; // allocates a character array with 6 elements - str[5] = '\0'

char *p = &str[0]; // p holds the memory address of the first element

while (p != &str[5]) { // loop until we reach the end. *p != '\0' is equivalent

cout << *p << "\n"; // derefencing p to get the current character

p++; // move p to the next element

}

p functions the same as begin while str[5] functions as end. This allows us to write generic functions that can be passed pointers for begin and end.

19.3. STL Algorithms#

The STL algorithms are a set of functions that can be used on a range of elements from a container. A range is any sequence that can be accessed through iterators or pointers.

General form: _algorithm_(begin, end, ...);

Algorithms operate directly on range elements rather than the enclosing containers.

Do make use of an element’s copy constructor, assignment operator, equality, not equals, and less than operators.

Some do not modify elements (e.g., find, count)

Others do modify elements (e.g., sort, copy, swap, transform)

//filename: algorithms.cpp

//complile: g++ -std=c++17 -o algorithms algorithms.cpp

//execute: ./algorithms

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

bool compareDescending(int a, int b) {

return a > b;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

//setup a uniform random distribution between 0 and 10,000: https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/numeric/random

double lower_bound = 0;

double upper_bound = 10000;

std::uniform_real_distribution<double> unif(lower_bound,upper_bound);

std::default_random_engine re;

vector<double> numbers;

for (int i=0; i < 100; i++) {

numbers.push_back(unif(re));

}

//cout << min_element(numbers.begin(), numbers.end());

cout << "total: " << accumulate(numbers.begin(), numbers.end(), 0.0) << "\n";

cout << "min: " << *min_element(numbers.begin(), numbers.end()) << "\n"; // returns a pointer to the element

cout << "max: " << *max_element(numbers.begin(), numbers.end()) << "\n";

sort(numbers.begin(), numbers.end(), compareDescending);

cout << "sorted: ";

bool passed_first = false;

for (auto a: numbers) {

if (passed_first) { cout << ","; }

else {passed_first = true;}

cout << a;

}

cout << "\n";

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

105 STL Algorithms in an hour: For many more details on STL algorithms. Optional viewing….