16. Iteration#

In previous notebooks, we discussed control statements (e.g., if) to decide which block of code to execute.

From a structured programming point of view, three basic building blocks exist to construct algorithms:

sequence (executing statements one after another)

selection (making decisions, control statements,

if)iteration (repeatedly executing parts of a program - also known as repetition)

This notebook examines the last basic building block - iteration.

Fortunately for us, computers do not tire or complain about doing the same thing time and time again. Many programming tasks are naturally repetitive. For example, suppose we did not know the formula for compounding interest. In that case, we could execute the base calculation (adding the interest earned to the principal) a specific number of times. Painfully tedious for us, just something else for a computer to do.

Returning to the Seven Steps, we looked for ways to generalize our algorithm in the third step. Finding repetitive patterns or behavior is another tool in this process.

Generally speaking, two basic types of iteration exist:

Indefinite: a code block repeats as long a particular condition is true

Definite: a code block repeats a fixed number of times.

In this notebook, we will examine the while statement as that is how Python implements the first type and then the for loop which roughly implements the second type.

16.1. Looping with while#

The while loop is a relatively simple looping mechanism that allows us to repeat a code block as long as the condition for the while statement remains True.

Suppose you are a fan of Getting Things Done and maintain a list of current “to-do items” while at your computer. A pseudocode example for processing that list might look like this -

while todo_list is not empty

- remove the first "todo" from the list

- process the "todo"

So the condition in this example is “todo_list is not empty”. In Python, we can state while todo_list: as todo_list evaluates to True if it has one or more entries and to False if it has zero entries. Within each iteration of the loop, we remove an item from the list - hopefully, we will eventually finish that list.

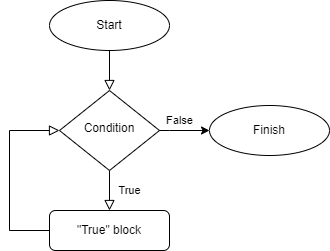

The while loop has the following syntax:

while condition:

block

If the condition evaluates to True, then the statements in the block execute. After the block executes, the entire statement repeats with evaluating the condition. This process repeats until the condition evaluates to False or the block causes the control flow to break out of the while statement.

Printing the numbers from 1 to 5:

1i = 1

2while i < 6:

3 print(i)

4 i = i + 1

1

2

3

4

5

As with the if statement, the condition is any expression that evaluates to True or False. In addition to Boolean values, this includes numbers, strings, lists, and tuples.

16.2. Break and Continue#

As with many other programming languages, Python has two statements that can affect the loop execution from within the block (as opposed to just the while condition).

With the break statement, execution immediately exits the block, and execution proceeds with the statement after the loop.

In the following example, we add a check that if i is divisible by 3, we exit the loop immediately.

1i = 1

2while i < 6:

3 if (i % 3 == 0):

4 break

5 else:

6 print(i)

7 i = i + 1

8print ("After the while loop")

1

2

After the while loop

Rather than exiting the loop immediately, the continue statement stops the current loop but moves the control flow to evaluate the condition at the top of the loop.

1i = 1

2while i < 6:

3 if (i % 2 == 0):

4 i = i +1

5 continue

6 print(i)

7 i = i +1

8

9print ("After the while loop")

1

3

5

After the while loop

In the above loop, we had to change the update of the variable i compared to the previous example. If we had not changed the value for i before the continue statement, the program would execute forever as the condition would have never changed. If you ran the follow code block it would loop forever as i is not incremented when the value is even.

i = 1

while i < 6:

if (i % 2 == 0):

continue

else:

print(i)

i = i +1

print ("After the while loop")

To avoid infinite loops such as the above, the statements within the while block should occur such that the test condition eventually evaluates to False.

16.3. While Example: Fibonacci Series#

The following code fragment prints out the first nine numbers of a Fibonacci series starting at zero.

Source: Python Tutorial

1a, b = 0, 1

2while a < 20:

3 print (a,end=', ')

4 a, b = b, a + b

5print (a)

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21

Several interesting details are present in these five lines of code:

Lines 1 and 4 both demonstrate parallel (multiple) assignment. The expressions on the right side of the assignment statement

=are evaluated left to right. After evaluating the expressions, the interpreter assigns each expression’s result to the corresponding variable on the left-hand side.We show a

whileloop, which executes as long as the condition (a < 20) evaluates toTrue.Notice that the final

print()statement prints the newline character.This loop is an example of a fencepost loop. Within the loop, we print a number followed by a comma. However, we do not want the last number printed to have a comma. Therefore, we treat the last iteration differently and print the value outside the loop. That last statement is the closing “post” in a fence line.

Many different approaches exist to solve the fencepost loop issue. For example, we can choose to special case the first “post” (loop) rather than the last. We can also add an if statement to print the separator after the first occurrence in the loop.

1a, b = 0, 1

2print (a, end='')

3while a < 20:

4 print (",",b,end='')

5 a, b = b, a + b

6print ()

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21

1a, b = 0, 1

2while a < 22: # logic change to show "21"

3 if (a >0):

4 print (', ',end='')

5 print (a,end='')

6 a, b = b, a + b

7print()

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21

Fencepost loops do not necessarily involve print statements - as programs process data, those programs may need to have special logic at the start or the end of a loop.

For instance, considering finding the maximum value of a list. We could check that the list contains at least one value and set the maximum found found to that. We then iterate from the second item onward to see if there’s another value greater than that one.

1a_list = [5,10,3,4,6]

2if len(a_list) > 0:

3 max_found = a_list[0] # special casing the first element of the loop

4 current_index = 1 # start looping at the second position

5 while current_index < len(a_list):

6 if a_list[current_index] > max_found:

7 max_found = a_list[current_index]

8 current_index += 1

9 print(max_found)

10else:

11 print("Empty list")

10

16.4. The Infinite While Loop#

A relatively common iteration pattern is to loop forever. In Python, such loops would have this pattern:

while True:

do something interesting

For a web server, the pseudocode for the application may look something like this -

initialize system

loop forever

wait for url request

process url request

A game engine may have an overall control structure, such as -

initialize game

loop forever

process any received user input

status = update game state

if status equals "stop", break out of loop

draw game state

process end of game

For the webserver, initialize system might become

read configuration file establish logging create server socket to listen for requests

16.4.1. Loop and a half problem#

Another common occurrence with while loops is the “loop and a half” problem. In these cases, we need to perform some processing for an indeterminate number of iterations.

Example: Continually read grades from a user until they enter a negative value which signifies they have finished entering grades. (The negative value operates as a sentinel, a distinct value to mark the end of a series of inputs or values. Sentinels need to be distinctive from expected values in the series.)

One approach would be to read the first input before entering the loop:

1total = 0

2num_entries = 0

3

4grade = int(input("Enter a grade: "))

5while grade > 0:

6 total += grade

7 num_entries += 1

8 grade = int(input("Enter a grade: "))

9

10if num_entries > 0:

11 print("Average:",total/num_entries)

12else:

13 print("no grades entered")

Enter a grade: 100

Enter a grade: 98

Enter a grade: 87

Enter a grade: 92

Enter a grade: 76

Enter a grade: 81

Enter a grade: -1

Average: 89.0

The downside to the above solution is that we have repeated code outside and inside the loop to enter grades. This example is relatively straightforward, but what if this repeated code was more complex? What happens when it needs to be changed? What if the programmer only changed the repeated code in one location?

An alternate approach is to use a “loop and a half structure”. This structure breaks out of the loop halfway when a particular condition occurs.

1total = 0

2num_entries = 0

3

4while True:

5 grade = int(input("Enter a grade: "))

6 if grade < 0:

7 break

8 total += grade

9 num_entries += 1

10

11if num_entries > 0:

12 print("Average:",total/num_entries)

13else:

14 print("no grades entered")

Enter a grade: 100

Enter a grade: 98

Enter a grade: 87

Enter a grade: 92

Enter a grade: 76

Enter a grade: 81

Enter a grade: -1

Average: 89.0

16.5. Sentinel Value#

Sentinel values can be used for more reasons than marking the end of an input stream within loops. We can also use these values as flags signify a certain condition has been met or not. For example, if we need to compare values as we loop through a list, we can use the sentinel to check whether or not a valid value has been seen. Within Python, programmers often use the None object as a sentinel for such a condition. Sentinel values for input data need to be a value that is not valid (e.g., a negative value or a string when an int/float is expected).

16.6. The for loop#

Python’s for loop differs from the for loops in other languages such as C, although it is roughly comparable to Java’s for each loop.

With this looping statement, we iterate over the items of an iterable - the sequences we have seen (string, list, and tuple) are iterables.

The for loop has the following syntax:

for variable in iterable:

block

1acc_schools = ["Duke", "Notre Dame", "UNC", "NCSU", "Wake Forest", "Clemson"]

2for school in acc_schools:

3 print(school)

Duke

Notre Dame

UNC

NCSU

Wake Forest

Clemson

As with the while loop, the for loop can contain break and continue statements

16.7. Generating Number Sequences: range()#

Python offers a built-in function range to generate a stream of numbers. We call range() similarly to how we used slices: range(start, stop, step).

Only the stop parameter is required. If the start parameter is not present, the range starts at 0. The range ends just before the value of stop. The step parameter has a default value of 1, but we can use any nonzero integer.

1for x in range(0, 4):

2 print(x)

0

1

2

3

1for x in range(4, 0, -1):

2 print(x)

4

3

2

1

Using the above code, use range() with just a stop number.

1# put in a just a stop number

2for x in range():

3 print(x)

0

1

2

3

4

Try some more examples yourself:

1# Enter a range from 10 to 0, skipping by 2's

2for x in range():

3 print(x)

4

5# Enter a range from 1 to 30, skipping by 3's

6for x in range ():

7 print(x)

10

8

6

4

2

0

1

4

7

10

13

16

19

22

25

28

From a space perspective, the interpreter does not produce the numbers from the range() function until needed, allowing us to create arbitrarily large series. However, if you make a list from a range, all the numbers are generated and stored in that list.

1list(range(1,11))

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

16.8. Indexes and Values with the for loop#

Generally speaking, it is an inferior practice to explicitly use an index variable to iterate through a sequence. However, use cases exist where the programmer needs both the index and value of an item while looping. We can use the built-in function enumerate() to wrap the iterable to use a for loop.

1acc_schools = ["Duke", "Notre Dame", "UNC", "NCSU", "Wake Forest", "Clemson"]

2for idx, school in enumerate(acc_schools):

3 print("{}: {}".format(idx,school))

0: Duke

1: Notre Dame

2: UNC

3: NCSU

4: Wake Forest

5: Clemson

16.9. Revisiting the Sudoku Board#

In the Lists notebook, we discussed how a Sudoku board could be represented as a list of lists.

Now that we know a bit more Python, we can more easily create the representation and display the board:

1# demonstrate creating a two dimensional list

2sudoku_board = []

3for row in range(9):

4 col_list = []

5 for col in range(9):

6 col_list.append(0) # let's use zero to represent an unknown square

7 sudoku_board.append(col_list)

8

9import random

10random.seed(42)

11for i in range(15): #Randomly place 15 numbers onto the board. may not be a legal sudoku puzzle

12 row = random.randint(0,8)

13 col = random.randint(0,8)

14 value = random.randint(1,9)

15 sudoku_board[row][col] = value

16

17# print the board

18num_rows = len(sudoku_board)

19num_cols = len(sudoku_board[0])

20for row in range(num_rows):

21 for col in range(num_cols):

22 print(sudoku_board[row][col],end="")

23 print()

007000090

500400202

000000000

000302057

000000000

000035000

100000000

000000000

900000000

16.10. Case Study: Revisiting the Systematic Investment Plan#

In the notebook on Basic Input and Output, we explored developing and writing the corresponding code to find the future value of a systematic investment plan. In that case, we assumed we could use an existing and well-known formula. However, what if we decided to perform the calculations manually? At the time, we did not have any mechanisms to repeat code. For example, if we had one hundred payments, we would have had one hundred statements, each adding a payment and the corresponding interest earned. However, with the iteration statements in this notebook, a Python script could easily do that work.

Problem: Write a function called future_value_sytematic_investment that computes the future value of a SIP for a given payment, annual interest rate, number of payments, and the number of periods per year.

We will repeat the Seven Steps design process:[1]

Manually perform this for three periods, assuming a 10% interest rate per period, and $100 per payment. (Steps 1/2)

$100 (just the payment) $100(payment) + $100(previous) + $100(previous) * 0.1 = $210 $100(payment) + $210(previous) + $210(previous) * 0.1 = $331

Now, let’s try to make this generic. (Step 3)

iteration 1: total = payment iteration 2: total = payment + previous total + previous total * interest iteration 3: total = payment + previous total + previous total * interest

Hmmm…. looks like our iteration stays pretty much the same, but can we make the first one look like the others?

iteration 0: total = 0

iteration 1: total = payment + previous total + previous total * interest

(Note: The previous total = 0, so total = payment as before

iteration 2: total = payment + previous total + previous total * interest

iteration 3: total = payment + previous total + previous total * interest

We can also factor out the previous total in each iteration:

total = payment + previous total * (1 + interest)

Now, how will this work for different values? We probably will still have overflow errors for large interest rates. However, we no longer are doing any division, so a 0% interest rate is no longer a problem. Negative interest rates smaller than -1 may cause issues. The number of periods per year needs to be more than 0.

inputs: payment amount, annual interest rate, total payments, periods per year

output: future value

algorithm:

periodic rate = annual interest rate / periods per year

result = 0

for total payments:

result = payment + result * (1+periodic rate)

return result

Let’s move on to coding:

1def future_value_sytematic_investment(payment_amount, annual_interest_rate,

2 num_payments, num_periods_per_year):

3 periodic_interest_rate = annual_interest_rate / num_periods_per_year

4 result = 0

5 for x in range(num_payments):

6 result = payment + result * (1+periodic_interest_rate)

7 print result

8 return result

9

10fv = future_value_sytematic_investment(100,10,5,1)

11print("Future value: ${:,.2}".format(fv))

Cell In[19], line 7

print result

^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'. Did you mean print(...)?

Sigh, the intermediate printing caused an error—another reason to use debuggers.

1def future_value_sytematic_investment(payment, annual_interest_rate,

2 num_payments, num_periods_per_year):

3 periodic_interest_rate = annual_interest_rate / num_periods_per_year

4 result = 0

5 for x in range(num_payments):

6 result = payment + result * (1+periodic_interest_rate)

7 print(result)

8 return result

9

10fv = future_value_sytematic_investment(100,.10,5,1)

11print("Future value: ${:,.2f}".format(fv))

100.0

210.0

331.0

464.1

610.51

Future value: $610.51

1print("Future value: ${:,.2f}".format(future_value_sytematic_investment(100,.1,5,12)))

100.0

200.83333333333331

302.50694444444446

405.02783564814814

508.4030676118827

Future value: $508.40

1print("Future value: ${:,.2f}".format(future_value_sytematic_investment(100,-5,5,1)))

100.0

-300.0

1300.0

-5100.0

20500.0

Future value: $20,500.00

Hopefully, the losses will not be too significant as large negative numbers are problematic. We learn methods to make our code more robust in a few notebooks.

Now, we need to go back and clean up our function to remove that test print statement. We should also add docstrings to provide help on this function.

1def future_value_sytematic_investment(payment, annual_interest_rate,

2 num_payments, num_periods_per_year):

3 """Computes the future value of a systematic investment plan

4

5 Args:

6 payment: How much money is put into the plan each period?

7 annual_interest_rate: What is the assumed interest rate for the plan?

8 num_payments: How many payments will the investor make in total?

9 num_periods_per_year: How many payments/periods are there in a year

10

11 Returns:

12 future value of the investment

13 """

14 periodic_interest_rate = annual_interest_rate / num_periods_per_year

15 result = 0

16 for x in range(num_payments):

17 result = payment + result * (1+periodic_interest_rate)

18 return result

1print("Future value: ${:,.2f}".format(future_value_sytematic_investment(100,0.07,360,12)))

Future value: $121,997.10

16.11. Case Study: Monte Carlo Simulation#

A common approach to determine whether or not an investment strategy will produce sufficient funds for retirement is to use a Monte Carlo Simulation of investment returns.

We can apply this method to our future_value_systematic_investment() function. However, we can randomly select return values rather than assuming a fixed interest rate. One possibility would be to select a random historical return of the DJIA. Another possibility is to use random numbers from a Gaussian distribution defined with a given mean and standard deviation.

Let’s modify our future value function to use a random interest rate annually. We will also simplify our method by only using one interest rate per year.

Jotting down some notes, we now have inputs: payment, num_payments, rate_mean, rate_stdev

The process appears the same, except the periodic_interest rate is now a random value.

We need to see if we can make this process even more generic. How have other people produced these calculations? In some situations, they assume an initial principal for the investment. So let’s add that too, but make this an optional parameter, defaulting the amount to 0.

1import random

1def future_value_sytematic_investment_random(payment, num_payments, rate_mean, rate_stdev,

2 initial_principal = 0.0):

3 """Computes the future value of a systematic investment plan, but use random

4 interest rates from a gaussian distribution.

5

6 Args:

7 payment: How much money is put into the plan annually?

8 num_payments: How many payments will the investor make in total?

9 rate_mean: assumed mean of the interest rate

10 rate_stdev: assumed standard deviation for the interest rate

11 initial_principal: what is the initial amount (value) in the account? Defaults to 0

12

13 Returns:

14 future value of the investment

15 """

16 result = initial_principal

17 for x in range(num_payments):

18 interest_rate = random.gauss(rate_mean, rate_stdev)

19 result = payment + result * (1+interest_rate)

20 return result

1print("Future value: ${:,.2f}".format(future_value_sytematic_investment_random(1200,30,0.07,.2)))

Future value: $40,614.62

We will get many different answers as we run the above cell multiple times. Some will be larger than the \(\$\)121,000 we computed before, and other results smaller. We cannot just take the number we like the best.

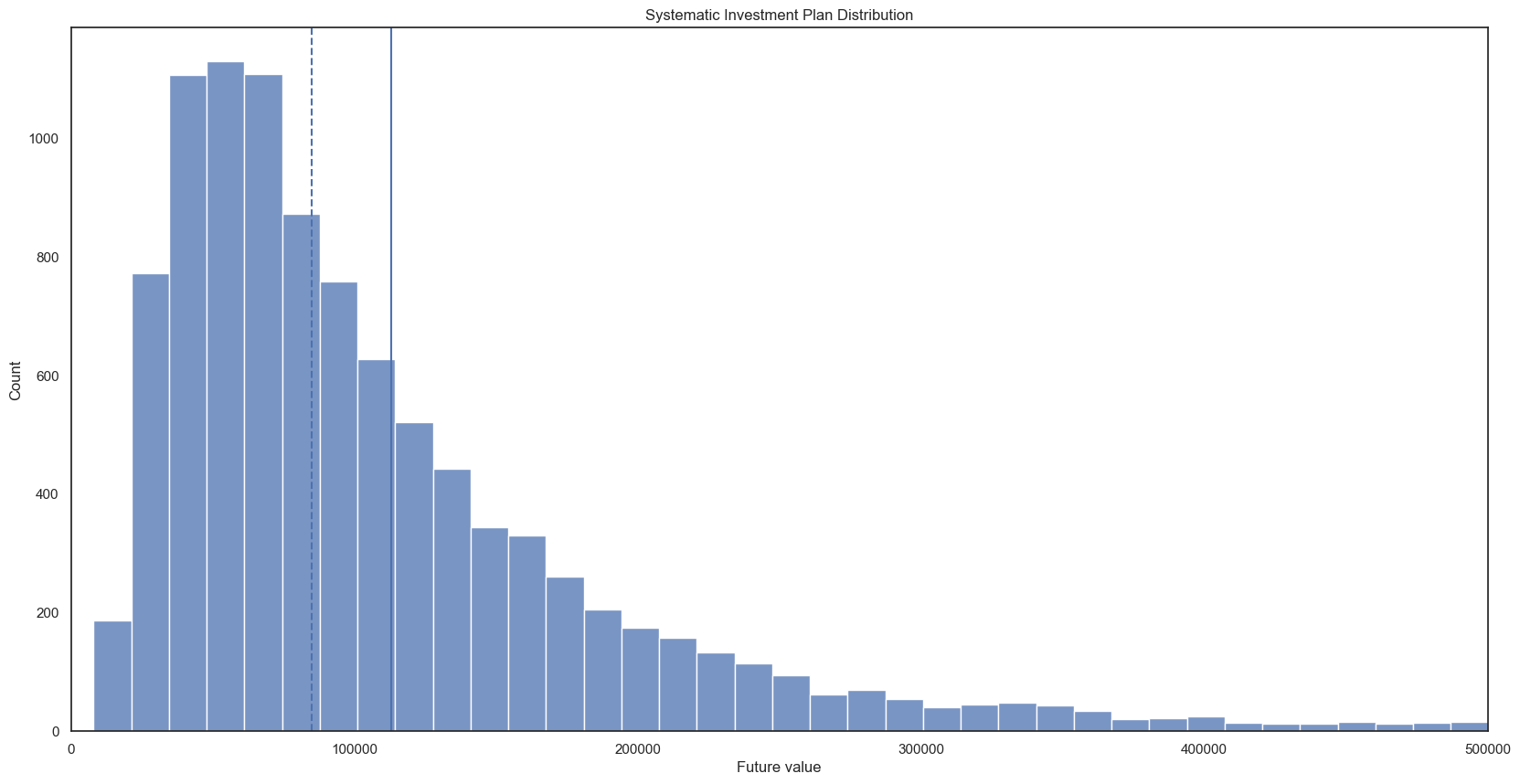

So to properly perform this simulation, we repeat this experiment thousands of times and then analyze the results.

1results = []

2for x in range(10000):

3 results.append(future_value_sytematic_investment_random(1200,30,0.07,.2))

1mean = sum(results)/len(results)

2print(mean)

113143.04994453333

1returns_sorted= sorted(results)

2

3median = returns_sorted[len(returns_sorted)//2] if len(returns_sorted)%2 == 1 else (returns_sorted[len(returns_sorted)//2 -1] + returns_sorted[len(returns_sorted)//2])/2

4print(median)

84802.52428862613

16.11.1. Visualize Results#

We use a visualization library, seaborn, to see the distribution of future values and the empirical cumulative distribution.

1import seaborn as sns

2

3# Establish size and style attributes for the visualizations

4sns.set(rc={'figure.figsize':(20,10)})

5sns.set_style('white')

1axes = sns.histplot(results,bins=50)

2axes.ticklabel_format(style='plain', axis='x',useOffset=False)

3axes.set(xlabel='Future value', ylabel='Count', title='Systematic Investment Plan Distribution')

[Text(0.5, 0, 'Future value'),

Text(0, 0.5, 'Count'),

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Systematic Investment Plan Distribution')]

1axes = sns.histplot(results,bins=100)

2axes.ticklabel_format(style='plain', axis='x',useOffset=False)

3axes.set(xlabel='Future value', ylabel='Count', title='Systematic Investment Plan Distribution')

4axes.axvline(mean) # draw a vertical bar for the mean

5axes.axvline(median,linestyle='--') # vertical bar for the median, dashed

6axes.set_xlim(0, 500000) # Distribution is long-tailed, lets chop off those rare values

(0.0, 500000.0)

1axes = sns.ecdfplot(results)

2axes.ticklabel_format(style='plain', axis='x',useOffset=False)

3axes.set(xlabel='Future value',

4 title='Cumulative Distribution Function: Future Value of a Systematic Investment Plane')

5axes.axvline(mean) # draw a vertical bar for the mean

6axes.axvline(median,linestyle='--') # vertical bar for our median, dashed line

7axes.set_xlim(0, 200000) # limit to focus on the lower returns

(0.0, 200000.0)

16.12. Seven Steps: Translating to Code#

This material has been adapted from Chapter 4 of All of Programming, by Andrew Hilton and Anne Bracy, https://aop.cs.cornell.edu/index.html

At this point in these notebooks, we’ve seen the basic building blocks for programming:

variables

input and output

sequence (executing statements one after another)

selection (making decisions, control statements,

if)iteration (repeatedly executing parts of a program - also known as repetition)

The following subsections present heuristics for converting your pseudocode algorithms into code:

16.12.1. Names#

When you explicitly name a value in your algorithm, that indicates a need to define a variable. While Python does not require us to define explicit types for variables, you should consider the most appropriate type to use. In Python, this definition occurs when we make assignments to the variable.

Give your variables meaningful names.

16.12.2. Input#

If your algorithm asks for input, that will typically involve receiving data from several different possibilities:

a text-based prompt with an input() statement

command-line argument (discussed in “Modules”)

file-based input (discussed in “Files”)

and many more possibilities (graphical interfaces, web pages, …)

16.12.3. Output#

Similar to input, if your algorithm displays a result back to the user, this may occur in several different ways:

print()for console outputWriting to a file (discussed in “Files”)

Web page

…

16.12.4. Computations and Changing Data#

When your algorithm has a mathematical formula or changes the data(values), compute that result and assign the result to a variable (or output/return the result).

16.12.5. Sequence#

When your algorithm executes a series of steps together, those steps form a code block. If those steps are repeated elsewhere in the algorithm, then consider putting those steps within a function to avoid code duplication.

16.12.6. Selection#

When the algorithm has some type of decision to make, that involves using some form of the if statement based upon the different conditions involved. Make sure you order those conditions appropriately.

16.12.7. Iteration#

When you find the algorithm repetitively performs a specific task, that indicates some form of a loop.

Within Python, if you iterate over a loop or a fixed series of numbers (e.g., from range()), usually that is some form of a definitive loop, and we will use a for loop.

If you iterate over a series of items based upon some condition, that indicates a while loop where the condition comes after the while keyword.

Be mindful of “fencepost” type loops in both types of loops. Often you will need to perform some initialization or special processing for the first iteration.

If the algorithm states stop doing this, that could indicate the need for a break statement to exit the loop. Similarly, if the algorithm needs to stop the current loop and start a new loop, that becomes a continue statement.

16.12.8. Answers#

If the algorithm produces a result, that may indicate a return within in function. Remember, functions are a named, reusable block of code that exist to perform a specific task. If that task has a result, return the result.

16.12.9. Complicated “Stuff”#

If your algorithm contains a line that is too complicated to be directly translated into code based on the heuristics in this section, you should look to break down those steps further. Additionally, this often indicates a need to put that line (and the broken-down steps) into a separate function.

When possible, seek to reuse existing code and libraries rather than create a new function.

When existing functionality does not exist, determine the function’s parameters and return values. Then determine the behavior that the function needs to contain.

Creating functions is an essential concept in programming as it is one of the primary ways we apply abstraction and encapsulation. With abstraction, we determine the fundamental parts of some tasks: input, processing, and output. Encapsulation puts those parts into a unit (a function) and hides the implementation details we may not necessarily need to know.

Functions also provide a way for us to reuse code. When we duplicate code through copy and paste, we make the code harder to understand and harder to maintain.

As an example, an issue one of the course instructors had in some production code was the following lines of code:

for publicKey in userKeys):

execute(client, "sudo sh -c 'echo \""+publicKey +"\" > /home/"+userID+"/.ssh/authorized_keys'")

This for loop copied a user’s ssh public keys onto a remote server for authentication. The > operator, when used for a shell command, causes a file to be created with the contents of the previous command. If the file already exists, the shell truncates the existing file, removing any prior contents. So every iteration of the loop created a new file. While only two lines of code exist in this example, these two lines were repeated elsewhere in the system. When a user reported an issue dealing with multiple keys and not being able to use those keys, a developer fixed the operator to >> in one location but not the other location. Unfortunately, this improper fix left a latent defect in the system that another user eventually discovered. The moral: don’t copy and paste code.

16.13. Composition#

One computer science principle that we will see in several different fashions within software development is composition. Composition is the ability to combine multiple items into a common unit.

If you think about the Lego example from an earlier notebook, we can combine bricks in a myriad of ways due to the design of the bricks. Similarly, in software development, we can combine things due to existing rules and practices.

At the lowest level, composition is demonstrated through Python’s syntax grammar. This grammar forms the rules of a legally syntactic Python program. As demonstrated in the portion of the grammar below, statements are composed of 1 or more statement in a sequence. (The + sign in grammars means one or more.). Each statement is either a compound_stmt or a simple_stmt. The simple_stmt ends with either a newline or ; (semi-colon). By having this composability, we can put together a multitude of different statements and expect them to work as expected.

statements: statement+

statement: compound_stmt | simple_stmts

simple_stmts:

| simple_stmt !';' NEWLINE

| ';'.simple_stmt+ [';'] NEWLINE

simple_stmt:

| assignment

| expressions

| return_stmt

| 'break'

| 'continue'

…

compound_stmt:

| function_def

| if_stmt

| for_stmt

| while_stmt

…

We also see composition demonstrated in nested function calls. In mathematics, we might see \(f(g(x))\). There, we compute the result of \(g(x)\) and pass to \(f\). In programming, we can often combine multiple lines.

1grades = [90, 84, 96]

2total = grades[0]

3total = total + grades[1]

4total = total + grades[2]

5average = total / 3

6print(average)

90.0

We can then compose these lines together:

1total = grades[0] + grades[1] + grades[2]

2average = total / 3

3print(average)

4

5# and then composing a bit further

6average = (grades[0] + grades[1] + grades[2]) /3

7print(average)

90.0

90.0

Simultaneously, we also need to be aware of how to generalize as well as utilizing existing functions. With iteration, we have seen how we can loop through a list. We can write a function that allows us to sum a list. Fortunately, Python already has a built-in function sum to do that.

We can also abstract computing the average a list into a function:

1def compute_average(l):

2 return sum(l)/len(l)

3

4print(compute_average(grades))

90.0

In the last line, we composed two functions into a single unit - call compute_average with an argument of grades, then take that result and pass it to print as that argument. Just like \(f(g(x))\)

In future notebooks, we will also see composition appear in object-oriented programming as we combine different objects into a single unit. From a larger-scale perspective, different components of a system can be composed. For instance, a web application is often composed of a database (to store data), a web application (to respond to user events), and a front-end application (to show the user information, often through web pages).

16.14. LLM Prompts#

Explain the concept of iteration in programming, using examples to illustrate its importance. Then, introduce the different types of iteration constructs available in Python (for loops, while loops, and advanced techniques like generators and iterators). Provide code examples for each type.

Dive deeper into for loops in Python. Explain how they work, their syntax, and how to iterate over different data structures like lists and tuples. Provide examples of common use cases and best practices.

Focus on while loops in Python. Explain their syntax, how they differ from for loops, and when to use them. Provide examples of scenarios where while loops are more appropriate than for loops, such as iterating until a certain condition is met or working with infinite sequences.

Provide financial examples of when to use definite and indefinite loops in Python. Define each loop type and explain why the loop choice is most appropriate.

Provide financial examples of when to use break and continue in python.

As I write a Python program, when should different concepts such as sequence, selection, and iteration be applied. Provide an example that combines all three. Show pseudocode first and then explain the translation to Python code.

Discuss best practices for iteration in Python, such as avoiding modifying iterable objects during iteration, using appropriate iteration techniques for different scenarios, and optimizing for performance and memory efficiency. Provide examples of common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

Implement a real-world project that involves iteration in Python, such as a web scraper, a data processing pipeline, or a file system walker. Walk through the implementation, explaining the iteration techniques used and why they were chosen.

Create a series of exercises and challenges related to iteration in Python. Provide sample solutions and explanations to help programmers solidify their understanding.

Explain what a fencepost loop is in programing, when it commonly occurs, and how to code such loops.

16.15. Review Questions#

What is iteration, and why is it important in programming?

Explain the differences between while and for loops. Which typically executes for an indeterminate number of times?

How do you iterate over a list in Python using a for loop?

What is the purpose of a

breakstatement?How do you create an infinite loop in Python using a while loop? Provide an example of when such a construct is used.

What is the significance of a sentinel value? How would such a value be used in a loop?

16.16. Exercises#

Write a function greater_than_x that takes two parameters: a list and a number. The function should return a new list consisting of any entries in the list greater than the number. Assume all entries in the list are numbers.

Given this list of closing stock prices, create functions to compute the mean, median, and standard deviation. Assume we have a sample, but you can also write your function to make this an optional flag. (Population vs. sample determines whether or not we divide by \(N\) (the number of elements) for a population, or \(N-1\) for a sample.

stock_prices = [ 123.75, 124.38, 121.78, 123.24, 122.41, 121.78, 127.88, 127.81, 128.70, 131.88]

Generate a range that produces the following numbers: 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20.

Create a guessing game. Generate a random number between 1 and 100. Have the user guess. Print a message if the guess is too high, too low, or correct. Repeat until the user guesses the number. Print the number of guesses. You can use the following code to create the random number:

import random

number = random.randint(1, 100)

Produce a compound interest chart for ten years using 1 to 15% for the interest rate. The x-axis should be the interest rate, with the y-axis being the years. Right justify the numbers. Assume $100.00 is the initial principle.

Read two strings from the user. The first string is a text block. The second string is a character, series of characters, or a word to find within each word of the text block. Split the first string by whitespace and then keep only those words that contain the second string. Join the remaining words together into a string, separated by a comma.

Given the following lists, generated random sentences by combining random words from each list in this order: article noun verb preposition article noun.

article = ["the", "a", "one", "some", "any"]

noun = ["boy", "girl", "dog", "town", "car"]

verb = ["drove", "jumped", "ran", "walked", "skipped"]

preposition = ["to", "from", "over", "under", "on"]

Capitalize the first word of the sentence and place a period at the end of the sentence. You can get a random element from a list with the following code: (the import statement only needs to occur once)

import random

random.choice(noun)

How would you repeat this five times?

Write a function that converts an integer to a string with a specific base.

def convert_int_to_base(i, base=10):

16.17. References#

[1] Andrew D. Hilton, Genevieve M. Lipp, and Susan H. Rodger. 2019. Translation from Problem to Code in Seven Steps. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Global Computing Education (CompEd ‘19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 78–84. https://doi-org.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/10.1145/3300115.3309508